4 JUNE 07

How has your first book changed your life?

59. Mary Biddinger

How did it happen that your manuscript was picked up by Steel Toe Books?

After being a finalist for a number of book prizes, I entered Prairie Fever in the Steel Toe Books open reading period. At the time my approach to submitting the manuscript was one of mass saturation, but I always admired Steel Toe Books for holding a reading period rather than a contest. I was also partial to the name Steel Toe Books, having spent much of my life stomping through the streets in big black boots. It seems I've been a Steel Toe poet in training since high school. I read Tom Hunley's description of the press in the Poet's Market, and thought, "Hey, that's me."

What do you remember about the day when you saw your finished book for the first time?

I think I got more excited when I received the contract, actually. The Steel Toe folks informed me of my acceptance by phone, and the next morning I started wondering whether I had imagined the whole thing. I kept asking my husband to confirm that Prairie Fever had been accepted for publication. I secretly flipped through the caller ID to confirm that a call had indeed come from Kentucky. When the contract arrived, everything solidified.

Tom Hunley passed along numerous electronic versions of the document, so when the box arrived on my doorstep I had a clear picture of the book in my head, but I was totally unprepared for the intensity of the cover's color and the creamy paper inside. I had imagined this day so many times in my head; you know, slicing open the box with a bejeweled golden dagger, my adoring public cheering from the lawn, banners in hand, the fireworks exploding in the sky as I cradled a copy of Prairie Fever in my hands for the first time, grinning as the paparazzi converged upon me. Only somehow it wasn't like that.

I was coming home from work. I saw the box on the front porch as I was driving down my street. I knew what it was. My kids were in the back seat being cranky. I schlepped everything from the car--children included--into the house. I waited for a moment, then opened the front door and picked up the box. It was heavy. Nobody was standing on my porch with balloons. I put the box next to our fireplace and waited until my husband got home. He got home. I opened the box with a slightly sticky pair of kitchen scissors. The book looked awesome. I instantly became terrified that it was replete with typos. I looked inside. It wasn't. I held a Prairie Fever for a few minutes and flipped through it. Then it was time for me to make dinner. I think we had spaghetti that night.

Were you involved in designing the cover?

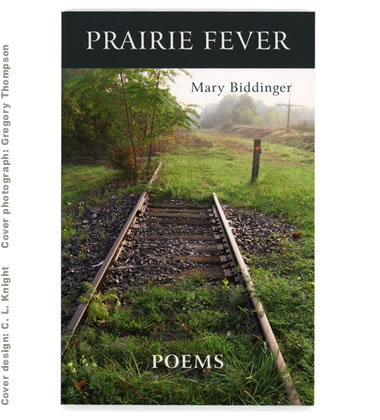

Yes! One of the things I loved most about working with Steel Toe Books was how much they welcomed my input on matters big and small. I always worried that whoever published my book would make me pick a cover I didn't like, or a very literal interpretation of the title: a Laura Ingalls Wilder look-alike with a thermometer in her mouth, or a blackberry pie cooling on a country windowsill. I wanted a photograph that illustrated the haunting collision of nature and civilization. I hoped for something green. I love pictures with a lot of little details that tell an implicit story. I also wanted a photograph from right here in Northeast Ohio. My corner of the state is full of hills and ravines and misty valleys, and that was something I wanted to capture.

My husband, Gregory Thompson, drove past a set of train tracks every day on his way to work in central Akron. These tracks were overtaken by grass and lined with sprouting junk trees and detritus. Obviously this was the perfect place for a photograph, and Greg suggested it to me as a possible cover for the book. He came home with a bunch of shots, and I settled on "Comeback" immediately. So many of the poems in Prairie Fever deal with train tracks: as a way out, as a place to drink warm cans of Schlitz with shady characters from homeroom, and as a locus amoenus. One time I did a public reading where I only featured train poems. It went on for thirty minutes. That's a lot of boxcars.

My favorite part of the cover is in the upper right corner, in the stand of foggy trees. If you look at the "r" in my last name you will see that it connects with a telephone pole that has an eerie resemblance to a cross. This was a coincidence, of course. Every time I stare at the cover I see something new in it. Who needs Hieronymus Bosch when you have an abandoned train yard of Midwestern delights to admire?

Before your book came out, did you imagine your life would change because of it? How has your life been different since?

Publishing this book has helped me move on and begin my new project--a series of poems that reinvents Saint Monica (patron of bad marriages, among other things)--and that's what I was really hoping it would do. On a more immediate level, publishing the book was a great relief for me, as I'll be applying for tenure in the not so distant future. As much as I liked being the oddity (how many journal pubs can one person possibly accrue without publishing a book?) I am very glad to have Prairie Fever on my vita.

Were there things you thought would happen that didn't? Surprises?

The only thing that really surprised me was how much I like reading out of the book. I am so happy with the book's font, and I've found it really comfortable to hold the book and read from it. At first I thought I should still print the poems out on pieces of paper, since that's what I'm used to when preparing for public readings. But the book feels good, and I can actually see it when I'm at the podium.

What have you been doing to promote the book, and what are those experiences like for you?

I was honored to read poems from Prairie Fever at the Switchback Books and Friends reading during AWP 07 in Atlanta, and that was sort of the world kickoff for the book. Since then I have been invited to read in a variety of places, and I was especially excited to have several readings in Youngstown, Ohio, a city that exemplifies the rust belt beauty that inspires me. I have also posted a lot of my experiences on my blog, The Word Cage, in hope that future first-timers will find some of the information useful.

What advice do you wish someone had given you before your book came out? What was the best advice you got?

I wish someone had prepared me for the surge of requests for copies. We sold out of Prairie Fever very quickly at AWP, and if I could do it all again I would stash fifty more emergency copies in my luggage. It felt awful turning people down, though I had a deluge of requests for signed copies through my website.

The best advice I received was from Kelli Russell Agodon, who told me to view book signing like writing out a thank you or "thinking of you" card. I had been seriously daunted by the idea of signing books for people, especially because I am a perfectionist (subject to irrational fantasies of spelling my name wrong) with carpal tunnel syndrome that can make my handwriting more artistic than I intend it to be. After Kelli's advice I viewed each book as a card, and my blood pressure dropped. I was in familiar territory. I am a devout thank you note sender by nature.

I also received much valuable advice from my fellow Steel Toe poet Jeannine Hall Gailey, and from my friend and colleague Elton Glaser, who read an earlier draft of the book and gave me some very useful criticism. The support of friends like Brandi Homan and Simone Muench and Jackie White made all the difference, too.

What influence has the book's publication had on your subsequent writing?

Prairie Fever's publication has helped me feel more comfortable taking risks and trusting my own judgment. I like poems that make the reader work. Midwestern poetry does not have to be straightforward or conventionally narrative. The poems in Prairie Fever are not traditional; you will find fragments, quick shifts, buckling pavement, but this is essential to the experience. When I was in school I endured many poetry workshops as the weird chick, the one whose poem was followed by several minutes of complete silence. I've had people tell me that my poems are not poems. I can't count how many times my classmates whined, "I don't get it," as if there was some secret punchline that evaded them. I had some professors who didn't offer much more advice than that.

I don't view the book's publication as vindication, of course, because since then I've learned that many people--editors included--do "get" what I am doing. But I am definitely more confident now. In the poetry workshops that I teach I make sure that nobody is subjected to the long silence. If it takes me seventeen reads, I will make sure that I am prepared to offer worthwhile commentary on every poem. I also encourage students to take risks and innovate.

How do you feel about the critical response so far and has it had any effect on your writing?

My book is still pretty new, so in many ways I'm waiting for the response, but the individual responses I have received from readers are amazing. I always hoped that there were people out there reading my poems in the litmags and wondering if I would ever publish a book. After Prairie Fever came out, I received a number of emails and blog comments from readers who were excited to finally get their hands on a volume of my work. Just thinking about that makes me blush.

I am also excited by the immediate response I have received from people at readings, especially from folks who I wouldn't necessarily expect to enjoy my poems. That's the thing. However I might experiment with language usage and narrative, I want to choose words that the characters in my poems would understand if they showed up at one of my readings and heard a poem for the first time. I want audiences to connect with the images and stories in the poems, and to think about them again and again. Not to disrespect the stereotypical beret-wearing, clove cigarette smoking poetry fan, but I get stoked when somebody's grandmother stops me after a reading and mentions a particular poem, or when an aspiring rapper asks me to sign his copy of Prairie Fever. That's when I feel like I am really getting my work out there.

I look forward to learning from my reviewers, because I feel like my understanding of the poems is limited by my intimacy with them, and my personal involvement in some of their stories. Jay Robinson taught me something I hadn't realized about my poems: "Biddinger's best offer us characters who mystify, not only because of their proximity to violence, but also because of their inexplicable and nearly unwitting participation in what endangers them." That makes perfect sense. I like reviews that articulate the things that a writer can't put into words. I hope that's what I do when writing reviews for other people.

Do you want your life to change?

I want to be able to spend more time writing. Of course, that is impossible. I'm a professor and a writing program administrator, not to mention the mother of two young children, so there will always be more work than time. But I do want to make writing more of a priority. I would also like to have a more creative lifestyle overall. By nature I am very left-brained, which can be a real obstacle for an artist. If there's a spreadsheet to update I will be tempted to leave a poem mid-sentence and immerse myself in Excel. I find many excuses for never seeing films. I don't bother listening to music unless I am in the car. I want to spend more time planting things in my backyard. I want to be more spontaneous and less neurotic. I do not, however, want to acquire more cats. We have five, and that's way more than enough.

Is there something you're doing now that you think will bring about a change that you seek?

Though I grew up in Michigan and Illinois, Ohio is my new homeland. I have my dream job teaching literature and creative writing at The University of Akron and NEOMFA (Northeast Ohio Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing) program. I own a late 1930's bungalow with an insane perennial garden and pachysandras that would probably withstand another ice age. I was recently awarded an Individual Creativity Excellence Award from the Ohio Arts Council. I can drive a few miles from my house and see hundreds of blue herons roosting in trees. My students write such compelling poems that I find myself rushing back to my office after class so that I can start a new poem of my own. I want to help nourish the literary scene here and give back to the community that has embraced me and made me feel welcome.

In addition to the work I do at The University of Akron--which includes facilitating writers' groups and bringing readers to the area, in addition to teaching classes--and serving as an Associate Editor of RHINO, I am starting a new literary magazine [Barn Owl Review] with the help of my husband and some other talented local writers. We've been talking about starting a litmag for years, namely a print journal of poetry and fiction that takes risks while still connecting with the audience. Being privy to the publication process with Prairie Fever pushed me over the edge, and I am now ready to take the plunge.

Do you believe that poetry can create change in the world?

Poetry is a laser. Fiction is a rib-spreader. Both of them are indispensable, but only poetry can do the most delicate surgery, penetrating with minimal damage. I do think that poetry can create change in the world, and I believe that it is essential to the world. Poetry is already there, in the ridiculous typo on a sign at the grocery store, or in the snippets of conversation drifting across a playground. We just have to find it.

:

A poem from Prairie Fever by Mary Biddinger:

Milfoil & Afterthought

There were four rooms. There were eight. You were in corners and under furniture, near my knees, reflections of your back in stainless steel. Suspenders, Florsheims and avocado linen. There was limestone halfway up, and I knew I'd crash into it if I could move fast. You thought it was a cold place. The light bulbs? It was all like helium to me at that point. I said someone should be taking pictures, the way we were sprawled on the hardwood or propped up on rattan sofas. One time in the airport we were both small and spun together in a leather chair chained to the ceiling. You touched my leg. Nobody was taking pictures, but that doesn't mean it didn't happen, or that we weren't in Frankenmuth five years later, at connecting tables but kept separate. A shed behind the school, or that storm sewer at the dunes, past the grasses, left of concession, the sand that felt like clay, like slip, how blond you had become, I hardly recognized. If you were here in this room you'd remind me of the guitar, the train platform, the silver Cutlass containing me and continuing on past it all. You said we'd go back. I was always a good runner. You said: the smoothest skin ever. We'd seen the skyline from two dozen taxis, our own legs on the bridge, from the grass, from the grass again, in the grass on my front lawn, lit by the cheap plastic solar lamps, from deep past the buoys of Lake Michigan and into the waterways connecting. We knew where we had come from, had that in common. In college I looked out the laundry room window and saw you between leaves, in a corduroy jacket. We're here, you said. There were blue sheets I used instead of curtains. Later I'd be in a hundred rooms with tin ceilings and slim wine glasses, or rectangular tables and cinderblocks and papers. In the subway window I'd look nothing but tired. I would try everything from milk to cactus in hope of turning you to milk and cactus and dark rafters and back again, so when I closed my eyes it was heat and every other color we described. The nights kept us like ants under plastic. I kept you in places that were cool and uncovered. You touched my face like it was years ago and just starting. I was busy fending off letters and drinking green tea and lying in a cool bath. By noon, everything was back where it had been. We're here and we're living, you said.

. . .

next interview: Kathleen Graber

. . .