30 JUNE 07

How has your first book changed your life?

67. Jill Magi

How did your manuscript happen to be picked up by Futurepoem?

I sent Threads in to their open call back in September 2004. I saw who the editors for that particular round were and thought they had some interests in hybrid, cross-cultural, and historical works and this gave me a little confidence that they might read the book in a favorable way. I had just been rejected from another press I admired, so I was pretty doubtful and began to think that the book was flawed in some way, too "content-driven," too much of a "family story" for the presses I was submitting to. And because the book contains about 30 visual images, I thought that many presses were turned off by the task of having to deal with that aspect. But I thought I'd give Futurepoem another shot, even though they had rejected another version of the same manuscript in the previous year!

So I won't forget the day in March of 2005 when I heard it would be published. It was the first day of spring and it was a gray, kind of depressing Sunday. I was in the bathtub taking a soak after going for a run in the rain and I was sitting there trying to decide if I would spend the rest of the afternoon actually working on a new revision of Threads or if I would just blow it off and watch college basketball on TV. The phone rang and I heard Jonny (my husband) speaking in a professional voice explaining to someone that I was "in the shower" and would call right back. Then Jonny came in and told me that it was Dan Machlin (Futurepoem's editor) who "wanted to talk to me about my manuscript." I got out of the tub pretty quickly but wanted to try and keep my cool, anticipating a kind rejection, like, "we really loved your work, but..." So I called Dan back and he asked me if the manuscript was still available and I think I answered, or at least I thought, "what, are you kidding me? Of course it's available!" After the phone call, I literally jumped up and down in the living room. Then we went out and had an expensive dinner--I had a big steak.

What do you remember about the day when you saw your finished book for the first time?

I was in San Francisco, getting ready to read at SPT and Dan Machlin made arrangements to ship a box of the books to them for the reading. The timing was tight so I was happy that the box had arrived. I remember seeing all of the books in shrink-wrap and not wanting to even unwrap a copy for fear of finding a mistake! So I just concentrated on the reading and didn't even really look closely at the books until about a week later, at home.

Before that day, did you imagine your life would change with its arrival?

I thought (and still do?) that my chances of getting teaching positions would improve. I have taught as an adjunct for ten years and I am not a reluctant teacher--honestly, I love teaching and I actually don't mind teaching "creative writing." I see teaching writing as a way to open students up to new kinds of texts, to expand communities of readers, expand notions of writing's relationship to thinking, perception, and experience. And somehow, teaching isn't difficult for me. As an adult literacy teacher in the early '90s, I learned from fabulous colleagues how to structure and run a class and so I call teaching "my bag of tools." It's just what I know how to do for money.

I was hoping--and still am--that "having a book" will allow me to experience better job security, a decent salary, and secure health benefits--in other words, a full-time academic teaching job. We'll see what happens--I'm quickly learning that the MFA is quite the credential and I have an MA in English because I never wanted to specialize too much--my degree allowed me to study many genres and even visual art. It'll be an interesting story about labor, the arts, and academia as it unfolds. And I'm skeptical anyway about artists being "absorbed" into academia. At times it seems more clear to just work, then make art--to separate the two activities--though I think a good liberal arts degree program benefits by the presence of artists and writers. So, finally, put it this way: I have some back-up plans if a full-time gig doesn't come through!

How has your life been different since your book came out?

Some things about my aesthetic confidence increased--after I heard the book was accepted for publication, I felt OK about my revision process and that I could write something publication-worthy. I began to feel more peaceful about my compositional choices and I felt a jolt of inspiration to continue with new projects.

The existence of the book has helped my friends--especially those who aren't writers--and my family to understand what I've been doing all these years. Now, finally, they can hold and read the project that's been keeping me in and up at night, taking up my vacation time, and making me tired when I worked full-time!

I also feel satisfied and glad that I stuck with this particular book project. I worked on Threads for ten years and it is the project that taught me how I wanted to write--it started out as a novel and then fell apart, happily, and kept accumulating historical material, visual material, and turning toward minimalism as I revised and revised. I was studying texts like Bhanu Kapil's and Susan Howe's and Myung Mi Kim's for clues about how to proceed aesthetically. And my friend John Calagione, the anthropologist, was continually pointing out articles and books on nationalism, literacy, and "the city" and all of these studies impacted the text. But I was mostly alone with the work and questioned my abilities deeply.

In January of 2005 I quit my full-time job as an academic advisor--a job that demanded lots from me and yet had no real flexibility or opportunity for "advancement"--so the news from Futurepoem made me feel a little surer that I had made a good decision. Also, earlier that March, Brenda Iijima told me she wanted to publish Cadastral Map, a chapbook of mine. So I began to feel "available" for poetry, ready to be committed to it, and perhaps "the community" could sense this? When I told my accountant the news, he told me that those around you sense when you are making time for art, that you really love it and want to do it. (I try to always believe and trust my accountant--is that the advice I have for new authors?!!)

Who the heck is your accountant?

My accountant is Howie Seligman--he's really the best!

But speaking of my accountant, and the energy of time and money, I also want to say that I'm lucky to own an apartment in Brooklyn whose value has tripled in the last seven years--and yet I'm aware how sinister that fact is because it means many people are being pushed out of the housing market even as renters. But my part-time teaching and subsequent availability for poetry is because we're living, in part, off of a home equity line of credit. And it was only because my grandmother, Elsie Harrop, who was always interested in my art-making and actually bought me my first computer, died in 1998 and left me with $10,000, that we could get a down-payment together for a spacious apartment that miraculously only cost $110,000.

Creativity with money, personal, and larger economies, and figuring out how to live, lurks behind every book of poetry--especially in NYC. I'm really fascinated by the demographics of art and like to make explicit, whenever I can, how I have time for poetry to the extent that I do. (Maybe it's a sign of being from New Jersey where you always reveal how much you paid for your clothes because no one pays full price! Or it's the residue of a working class tendency in my family to apologize for moving into the middle class, for the decision to "make art"?)

Where does Sona Books fit in? When did you start publishing the work of other poets and why?

I began Sona Books in 2002. I was noticing that many of my friends were writing wonderful things and were not even trying to get their work out there so I thought I'd create a forum for them, and in so doing, I would find a way to connect with the larger "poetry scene." One of the first people I met was Matvei Yankelevich and then I met Anna Moschovakis and they were welcoming to me. They put together a small press fair in 2003 and offered Sona Books a table and I sat down in between Brandon Lorber and Brenda Iijima and they were kind of puzzled, but in a good way, asking "who are you? where did you come from?"

Anyway, back in 2002 I was thinking about Anne Waldman's "edict": poets need to publish each other. I had just begun to put some of my own work together in self-published chapbook form and was interested in the visual aspects of putting together a book and so it all just came together. Turning my attention to the works of others helps me understand revision, line breaks, the placement of work on a page. It also helps me realize that most work is good, solid--writers themselves are often too picky. If you are engrossed in what you're writing, if you read and study good poetry, don't hesitate, get your work out there! It's usually better than you think it is! So as a publisher, I'll gladly publish work that even to me looks like it might have some problems. I'll talk to the writer about the work, but always encourage them to put it out there and then see what they see in the piece as time goes by. Chapbooks can be this for people--a blueprint for something else perhaps more developed.

I want to say that running Sona Books is kind of playful for me. When I was a kid, my sister and I used to make up fake businesses, create sales receipts, create an office setup and phone, take orders, etc. and so now I get to run something that contributes, in a very small way, to the furthering of poets and poetry, but it feels like play.

How do you feel about the critical response to Threads so far and has it had any effect on your writing?

First, the "non-critical" feedback I've heard has been important and touching. Like this, from my friend Mary who wrote to me last week: "I had a wonderful Mother's Day. The best part was sitting in St. Luke's garden on a perfect spring day as my daughter read aloud to me passages from Threads by Jill Magi." And from my friend Eldy: "Thank you so much for the book. I've started to read a little and can't help but think about the stories my relatives told of the Japanese occupation of the Philippines during World War II and the Adventist conversion of my own grandparents on my father's side." I also heard that Jonny's grandmother, who lives down in Knox County, Kentucky, liked the line "drunk on miniskirts" on page one and she wanted to know if this was going to be a funny book.

Then, on May 3, just a day after I complained to my friend Joanna Sondheim about the silence that rolls in after your book is published, she emailed to tell me that Ron Silliman had written pretty favorably about the book. In his write-up, he pointed out that it was a multi-disciplinary project and I'm glad he wrote that. Silliman's comments have made me realize that yes, I view my works as projects and I am not wedded to poetry as a form in particular. This has inspired me to keep working on a new project called SLOT which is about responses to landscaped and inscribed social memory--it's about museums, monuments, and memorials. The project will contain visual elements and when I perform from it, I'm including the works of sound artist Jonny Farrow (my husband) and I'd also like to include multiple readers and voices.

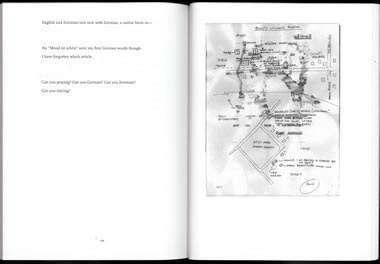

On that very same day that Silliman's note came out, and within minutes of reading his blog, my father called to tell me that my uncle, Eino Magi, had passed away. Eino is one of the voices in the book--page 93 is a transcription of a letter he wrote to me. He was one of the last family connections to real fluency in Estonian; my father, who also speaks Estonian, now essentially has no one left to talk with in Estonian. So on that day I understood something about the purpose of my book in our family, and I felt happiness that strangers were now possibly sounding out some of the Estonian words in the book.

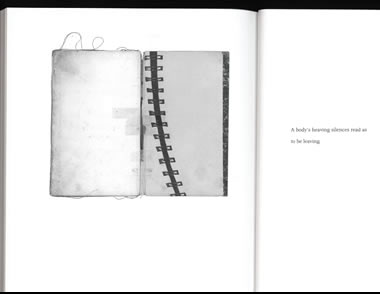

I guess this task of contemplating silence is a direct result of having a book published and it's having an effect on how I think about text and art. I understand better now that texts do not necessarily break silences, but that they remind us of the existence of silence and that silence is not necessarily negative. And maybe I'm also understanding that, at times, when the silence seems too much, the universe sends something along--be it a note from Ron Silliman, or an email from a close friend, or sad news about a loved one dying, reminding us how small our selves and artworks are in the scope of things.

Do you believe that poetry can create change in the world?

Yes. But happily, the change poetry makes is probably impossible to measure.

Lots of different kinds of actions create change in the world, but I am particularly interested in poetry's emphasis on relationship, reflection, and smallness. Reading a book, sitting with it, is a quiet and reflective act, yet it's collaborative. Books that invite a participatory meaning-making relationship between writer and reader--maybe they're called "experimental" and here I'm thinking of Juliana Spahr's thesis in her book Everybody's Autonomy--these texts, in particular, facilitate shifts in consciousness, shifts in awareness that might be imperceptible to others and to the world. They also invite a way of being with language--being flexible, being involved, becoming an agent of language and therefore understanding the malleability of one's own thoughts and perceptions.

Writing poetry helps me to understand that all webs of relationship--from the very small relationship one has with oneself, with a book, with language, to increasingly larger circles of relations with family, friends, colleagues, neighbors, city, county, country, policy makers, politicians, strangers, world--all relationships are important and when the space for reflection and quiet is facilitated in relationships, harm can be detected, an opportunity for intervention is created, small violences can be remedied before gaining speed and becoming larger ones--change is possible. Art can facilitate this; poetry facilitates this on the level of the individual utterance.

I've been involved in larger-scale "activism" that frankly didn't "work." I look back and can see that my actions, honestly, were often driven by hubris and anger and naivete more so than by knowing and alliances and kindness. At a certain point, I turned to poetry and art-making to understand myself and others. It's hard to conceptualize, but the smallness of interactions around poetry and other kinds of reflective arts and practices can, I believe, make real the possibility of informed, kind, and intelligent large actions.

But, at the end of the day, I think it's OK not to know how or why poetry and art matters, but to like making it, reading it (which is a kind of way of making poetry), and to extend that kind of creative grace and playfulness toward every relationship one has with language and self and other.

I also think it's important to understand that making art and poetry doesn't mean you are a "better" person or interested in general betterment and neo-enlightenment projects--poetry encompasses everything that we are and doesn't look away. And, in fact, art has often been at the service of fascism and some really bad ideas. So art is ambiguous and delivers no salvation from the actual world. Still, we participate, inviting perceptual shifts and so I think it's important work.

Does this all sound mushy? Well, maybe I'm putting it into words to make it a little more solid--or maybe to make it even softer, some thoughts and ideas that can be revised by anyone reading this now.

So thanks, Kate, for asking!

:

seven pages from Threads by Jill Magi:

From far away.

Soul to bury.

I can't breathe anymore.

To sprinkle. I'll sprinkle some cold water on you

to rescue--

clever (leaving, to save) though clear regret.

Blue sea, clear sky, fresh air. I don't regret coming here.

:

Other prisoners sew my poems in their clothes.

But they were sent there for hiding me in their farm.

I had no right to ruin their lives.

I built my bunker on the latticework ceiling.

A learned man, a lost letter.

A mouth stuffed with clouds.

:

:

Dear--

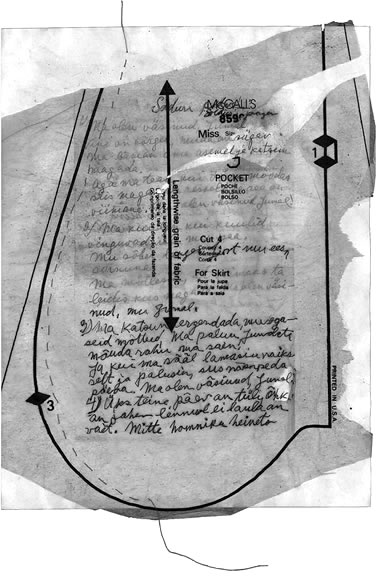

I found the poems by Gmother we talked about. In translating them I took some "poetic" liberties with English grammar and syntax, as you will notice. In doing so, I felt, I was able to convey some of the mood and rhythm of the original language. I also found a sheet of paper with the translation of the Estonian national anthem and a poem by Lydia Koidula on it. The latter I attempted to translate quite literally. The word "isamaa" in literal translation is "fatherland." But "fatherland" sounds too tough, too robust in English, maybe too Germanic. To the Estonian mind "isamaa" is more tender and loving than "fatherland." Thus "native land" seems a more appropriate translation. Besides, self-respecting Estonians would not, God forbid, be identified with Germans, although they are a mixed race with a good dose of German blood in them. I also found the copy of a letter from Gfather with a translation of another Estonian poem in it. The poet--Juhan Liiv--incidentally attended the same high school in Tartu that I did, although he did it 100 years earlier. Juhan Liiv's poems are very melancholy. He suffered from depression and eventually committed suicide.

Greetings to you and J.

Love--

:

"The grandchildren" (we) "only point at me when--"

this I am told she wrote in letters from (my) America

sometimes in code (the use of certain Bible verses)

responding to pre-printed Soviet envelopes but

Estonia has now gone over to the common western style

and would not write Dear unless they meant it.

:

One who comes.

One who washes.

Who wishes.

Seer, prophet.

One who is dying.

One who is doing.

:

Rummaging through boxes of my anxiety in the basement looking for his naturalization papers for many years we call him "a man without a country" and he always answers "don't make fun of the poor refugee," laughing. The meaning of natural.

. . .

next interview: Shafer Hall

. . .

home