10 AUG 07

How has your first book changed your life?

82. Miguel Murphy

Your first book has been reprinted? Tell me about that. Who published it initially?

My book--what a fantastic thing to say, like the first time newlyweds must use the words "husband" "wife"--or the way new lovers first use the word "we"--

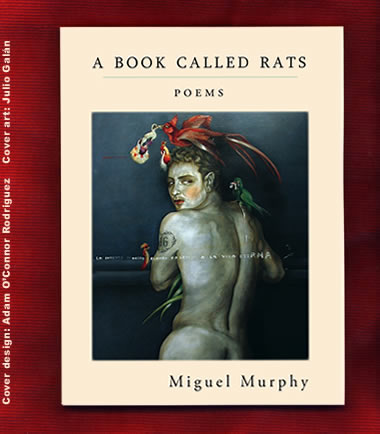

A Book Called Rats was selected by Michael Heffernan for the Blue Lynx Prize from Lynx House Press in 2002, and was published the next year, in August 2003. Lynx House was a small poetry press that published books since the year I was born, 1974--(they published Yusef Komunyakaa's early book, Lost In the Bonewheel Factory). In August 2006 I was contacted by Eastern Washington University Press, informing me they had acquired Lynx House, and would now be publishing the winners of their Spokane Poetry Prize as Blue Lynx titles. My book sold out, and they wanted to re-print it.

Publication is always such an unreal joy. The news is almost better than the thing itself. I was emotional about that first edition--stunned on the beaches, stupid with joy, though I'm actually much happier with the printing this time around. I felt that what ends up in print is the real prize, the garland, you know? --and it is! The book is a kind of mirror that should reflect not your actual life, but your imagined life. There's something beautiful about a book that is your own--whether you hold it or hide from it. I did a little of both with that first edition. It's beyond me how it's gotten a reprint, because I literally have done nothing to promote it. Not one reading. The little bastards ate their way through!

What do you remember about the day when you saw your finished book for the second time?

The news of a second printing is as stunning as finding out you've been selected for a prize. It lights you, accidental. Lustrous. I can't even begin to convey my naked absolute surprise. I thought last summer that it was a fluke, there must be some catch, this is not really going to happen. There was a minute after signing the new contract that I was informed they had found some copies of the first version, and I thought, oh. That's it. This will never happen. I sort of forgot about it. Then late spring things got rolling again. Everyone at EWU was my friend and accomplice--they let me fix some mistakes and help with the new cover.

Steve Meyers the marketing guy had sent me an e-mail telling me he had a copy in his hands and was mailing them to me, so I had an eye out all week. The day I got the package I was exhausted. My bicycle had been stolen so I had just walked home after 6 hours of summer school. I ripped it open like a piece of chocolate--and there were two copies of it with a little post it over the ass-crack, "hoola optional." It's just perfect. I called all my friends, went to my parents' house to show them. I sent my press a thank you box of gourmet chocolates and a note that steals a line from Willa Cather--that I felt "deliciously yet delicately fired"--I feel like I've won the lottery! Like I've fallen in love! It's unquantifiable this happiness. It's transformative and too big--This is the book that is my own. Proof of my existence. My heart's artifact.

Were you involved in designing the cover?

My mother is an artist and I've always had a very particular vision of the book as an object. I knew I wanted a say in the cover. The first time around, the cover I selected didn't work out. This time it was the first thing I asked for. I was told I could send them any images or ideas, as EWU was giving it a new ISBN and a new cover, if reasonable, was possible. I stalked the Mexican painter Julio Galan, a contemporary artist, one of the thorns in my crown of favorites--the same week he gave me permission he died. I then went through his family for permission and they've been terribly gracious. I couldn't be happier than in their debt. The painting itself speaks to the ugly erotics, the sad sexual glamour, the dangerous appeal of the darker poems in the book.

The cover is important. I think about how presses market while I comb the bookstores, and I feel like the good covers are more than marketing tools. I think as artists we need our books to really stand as beautiful objects. The cover is more than a mirror. It's a shield, a door, a flag. This is the thing that stands for us, for our poems and their struggles. I'm intensely grateful to Julio and his family, because my poems really do speak to his work. This sort of dialogue creates a kind of brotherhood between image and language, a symbolic kinship that makes the experience of buying, holding, reading a book complete. I remember a few years ago working at The Bilingual Review/Press and seeing other authors upset by the choices a press makes in a different interest than the author's artistic vision. For an author it can be both frustrating and disheartening. Suddenly your book isn't yours. I think it's important for writers to feel like the book is their own, a possession, but also a creation, something they can gift. I really feel that I share this book with the staff at EWU, who have been so open and supportive of this as a vision of my creative life. It's really "our" book, and the final cover, my cover, exemplifies that.

Before the day you saw your book, did you imagine your life would change with its arrival?

When I was in school, the idea was if you could get a book published you could get a job. This isn't necessarily the case. The job market has changed dramatically in the last 20 years. There are more adjunct positions than tenure, so not only do you compete with the yearly flood of new MFA's and now PhD's in creative writing, but also those of us with one or more books published. This has really changed my idea about the value of poetry and the different lives of poets. I know that I envy poets who are regularly published in "smaller" ways, yearly chapbooks, oodles of literary publications, even though the book prize eludes them. I wish there were a better way to share this, because I think our solitary natures can suffocate the poem, and there are brilliant poets at work who don't yet have a book. These other publications, in my own life, are founts of great courage and inspiration.

I think of Roethke, "I'll make a broken music or I'll die" and then I'm inside this religious pursuit, which is fanatical and awake. It's not easy, because people don't understand it, especially in Los Angeles, where the cosmetic self is god. No one seems to understand that to write a poem isn't about inspiration as it is about a daily struggle with craft. People want to know you've written a novel, or an article, or a screenplay, but poetry? It's juvenile and corrupt and impractical and it doesn't make sense. It certainly isn't going to make you any money! But I have this calling for it. Poetry is where I really seek to live. The anxiety, then, over whether or not you can be "successful" can be overwhelming.

The book is it. It's the thing that proves your fervor, your discipline, your perseverance, your ability. But the life of poetry isn't always satisfied by this end. It wants to speak to struggles that are private and difficult to articulate--so it's a terrorist. It's an activist. It survives into hiding. It wants to blow something up. It wants to rob your nights and amputate you from your contemporary sleeps. It wants all of your attention, more than you've got. In the end, poetry is the outrage of beauty against Nothingness. Sometimes this doesn't change your life with a job, or even with a book, but it marks your experience. It means that your experience for a moment is lit up by a depthcharge. Poetry is that bomb, and that consequential light--it's an xray flash radiating the vagueness of our living.

Has your life been different since?

Yes. Now I exist. If the first printing was a condemnation of my faults, this book is heroic! Monumental--I should be buried with it.

Life gets in the way. Everything has been different, but it had nothing to do with the book. The book had a life of its own. It was off somewhere doing shots, getting laid. I was reclusive and insecure and chasing down seansinger and writing creepy emails to ai and paisley reckdal--I was messy and loud and heartbroken and my book was savvy. My book didn't like me much. Only now, with this new print. This one is mine, it sleeps with me. We're in love. Yes its different. Its evermarvelous--

Were there things you thought would happen that didn't? Surprises?

I thought my boyfriend would take me back. I thought I'd get a real job. I thought I'd be dripping with money. I thought my family would disown me. I thought I would grow up. I thought it would make publishing poems easier. Surprise! AWP is full of assholes with books, and you have to be able to face the important brag of it. How you feel about your book really determines what you'll do for it. This second printing is a real gift. It's like finding out your dick isn't small. Now I'll take it anywhere, shove it in your face. Tell you it's big. Ask you if you want to touch it.

It is big. I want you to touch it.

What are you doing to promote the book and how do you feel about it?

This is the real deal, it's my own, I don't care if anyone else likes it I like it I like it A LOT!--The reality of it is resplendent--I am a saint. This is my miracle.

As far as promotion, this time around I'm just beginning to get advice. I still can't believe that it did so well in its first printing without any promotion at all. If anyone has advice I'll take it--It's the second printing but for me it feels like the only printing. I started a blog last winter and I feel like there's another community for building a network that might support not only you as a writer, but your work in its life, apart from you. When I was writing some of these poems the internet was just beginning to be the necessity that it is. Now online journals and blogs are as important, if not more effective, than print sources in terms of reaching audiences, and there's a real loyalty I find, a real engagement on these things.

On the internet you participate in another kind of fiction, a choose-your-own-adventure, a new kind of theater where a good rule of thumb is people lie. But these are wonderful lies! And then you can imagine your book running off in the arms of all these liars, all these variable Hamlets--and this is a great mental pleasure. The internet is really just an extension of your life's fiction.

Basically it's really wonderful--I mean the experience of having a book. It blinds me. I love it so much I'll tell anyone, do anything--brag, sell myself. It feels like the impossible happening. I'm so proud of this book I really feel like I can admit it is my own--which is something I couldn't do before--and more--I want other people to have it, look at it, hold it, read it.

I begin with my family. I took a copy this last week to my grandfather's funeral to show everyone. Have I crossed the line? My grandmother on my mother's side is really the only other person who adores the book as much as I do. She's in her 80's from Sonora, Mexico. She lingered over it, like some relic in a church she wanted to slip into her purse. I gave it to her, the first copy. She clutched it to herself and said I just love it. I'm going to show all my friends. This is a real treasure. Then she sort of curled around it, pulled her dark rebozo down around her shoulders, held it over her chest and eyed everyone, smiling seriously.

I've spent so much time worrying in the last edition about how people, especially people I know, will respond--I was worried--this kind of attention felt incestuous--but this time I can't help myself! I have the strongest sensation that this book is a relic of my existence. It's really something...

What advice do you wish someone had given you before your book came out? What was the best advice you got? What advice would you give to someone about to have a first book published?

I can't say that I really got any advice the first time around. It was all very clandestine and lonely. I ultimately shared the news with very few people. Maybe someone told me to enjoy it, but it was really impossible at the time. The advice I wish I got is the advice I'd give:

The book is what we live for--In print, our words are remains. They're ashes. They're us, a version of us that matter. The book is what we work so hard for for so long.

You have to really sleep with your press. Be co-dependant. Call, email, stalk, harass them. Make friends. Your press will have slightly different interests than you, so you have to be pro-active and thrust upon them your vision, from the cover to the editing. Don't be scared of them, or of pressing a point that you're unsure of. If they're good, they'll accommodate you--in the end I believe that the press has at heart the care of your work. No one wants a book they can't be happy with, but once it's printed there's no going back! Haunt them until you feel sure that you have fulfilled your duty to your work. We struggle so much for these little bastards, you know? It might be years before our poems end up in a book, after insomnia and tears and countless self-hatreds, so the last thing you want to do is to abandon them too soon. When it's in your hands. That's when your responsibility to the writing of the text is over. Marketing blah blah, you'll deal with that later. You want a beautiful relic for your life.

What influence has the book's publication had on your subsequent writing?

Writing is always the difficult part, and it doesn't get easier. I wanted to move beyond that book, to get better. Writing in the real world is different than writing at school. The university is a great safe bay, where your only goal is to read and write and attempt and think and dream. The struggle is to do these things while you're suffering over rent, debt, and rejection. For me that meant trying to write in different styles, or experimenting in ways that I wouldn't otherwise. After working a ten hour day doing temp work, it meant making what I could out of sheer will power, and that doesn't always equal a good poem. It also creates another struggle, as you're being weighed against your friends and sisters who've become economically successful. I've had people ask me when I'm going to give up playing around and get a real job.

Being in the real world has really cultivated a hardened sensibility in me as a reader. I want the poetry that I read to deliver something that really burns. I want to walk around while it's still smoldering against me. It has to, to matter, to save me from mediocrity, from the wallpaper of capitalist living. So I've found myself writing against the kind of poem I read, perhaps the kind of poem I fail, in journal after journal. Maybe this is a good thing (now that I write it) but it can feel debilitating. The problem is you're never really a poet until the next thing you write. And you're never really a writer until the next thing you publish. So you spend your life--at least I do--with infinite broken attempts.

Helen Vendler has written about her vocation as a critic. Other poets have asked her whether she ever wrote verse, and she says something about a different kind of dedication, a different need--that poetry demands a kind of restlessness, a kind of desire that wasn't true for her. Can a poet succeed without publication? That's a bitch of a question! Plath said that nothing stinks worse than a pile of unpublished poems. The book gives you a taste of something possible, something you want to keep doing. It casts its own spell on you.

How do you feel about the critical response and has it had any effect on your writing?

I was thrilled by the blurbs I was given by my old teachers, because I wasn't ever sure that they actually liked my work as a student. I think we need our champions, and to find out they were mine was a great compliment. These things bolster you up, make you feel like you can do it again. They make you brave. They are a genuine help.

There's only been a single review by Rigoberto Gonzalez in the El Paso Times and it was very kind. I blushed all over it. It helps the way getting a poem published helps--it's a success, a confirmation, it makes you courageous--you feel as if you really are a writer! You feel as if the last fifty rejections, or hundred and fifty rejections, explode like balloons. It's a celebration and this can carry you for a time...

I don't know, I sort of feel that critics can only be regarded with suspicion--even when they're favorable. What they're really doing is marking their engagement with your text. They're writing for themselves, to hear themselves speak in a language that befits their own intelligence, their own ability to read and listen and place your text in context with other texts. This is useful for us as readers because we can relate to whether or not we might enjoy a book, or understand it's value as literature, but for the most part it's useless to us as authors, because it fans the ego of the critic, and doesn't necessarily offer us real direction or advice--I say this as someone who lately publishes reviews--the purpose of the critic is to mark the pleasures of a text in a larger literary tradition. But as an author it does you dangerous good to flame your ego and it certainly doesn't help to smother it. I think instead we need that smaller community to encourage us, and talk us through our work, even if they're lying. A flawed text may be nothing but an attempt at something brilliant, something you haven't yet written --so for the author, criticism is both a disease and a drug.

On the outside I think any criticism is good press. We have to be like Madonna, admit everything. Own everything. Flaunt it. Sell it.

On the inside we have to pretend to ignore it altogether.

Do you want your life to change?

So that my monstrosity is cured? So that my deformities are healed? No. Never. The ruins here are beautiful.

Is there something you're doing now that you think will bring about a change that you seek?

I don't believe that poetry, or Art, has a purpose--I don't think that it can heal. But I do think it can tear down our elegant ideas about ourselves and that it can reveal the gruesome part of our nature, which doesn't deal well with mortality. Art, especially poetry, is nonsense, if you want to have a practical life. It's impractical, precisely because it forces us to consider our mortality, and our love, and the irresolution between the two.

Poetry is more an accusation, a means of rebellion--it illustrates the difficulty we have in this world to love the temporary above all else--our time is lightning in a wave--and to be unable to define our feelings to this changing, ever-leaving existence, memory and body. It's a mean anchor to the transcendental, to existential worry.

I guess the work of poetry is to get off on the world, as it is. Because it's beautiful and we love it best and ardently and because it's leaving us for good and because this is what we know. Because it faces these truths it enriches our lives. It can't be governed by the idea of permanence. It's inquisitive and vulnerable and open to human flaws and disaster. Its responsibility is to see, paint, enact, desire, summon, touch, disappear--

I seek a new poem. I'm holding still and thrashing about--I'm wringing my hands and closing my eyes to listen. I'm up late, I'm downing my fourth cup of coffee, I'm stuffing my mouth with a chocolate, I'm stripping down to my sex and my childhood and my first love and my family, I'm scratching a few words on the wall in the dark, I'm listening to the war news on the radio, to the dogs bark, I'm going AWOL, I'm running out to the beaches where the sea is black incantatory--I'm hunting the moon, dreaming of my thirst, working toward it because I want to really live--I want to hear the eucalyptus leaves shuddering high and inside--I want to condense this mania into a simple thorn and berry--I want to express the exquisite--to be happy for a moment that is crumbling me rapidly out of my own blood existence!

Do you believe that poetry can create change in the world?

Poetry is a gun. You put it in your mouth.

:

2 poems from A Book Called Rats by Miguel Murphy:

The Devil's Arm

The child violinist dreams the ocean

reaches up to him through a window's

pitch black gape--a red

arm and violin strings

throbbing down the length of it.

He tells his mother the devil

fills his mind with songs

that make the maestro

shake with fear.

He has sent me

home again, the boy cries,

to prostrate myself

before our Holy Virgin, Beacon

and Star of the Sea.

Without thinking, his mother grips

the violin by its stem

and laughs. Come play

the devil's tune--

the maestro may not hear it

but his nights are no less humid

with desire. We will

be satisfied.

And the quick note

sliding down

the violin's

spine

reaches from her fingers

in the boy a slender pleasure, darker

than memory's wine. The boy opens

his already opened eyes, as over water

where a man in the distance

is insisting his enemy worship him...

Capricorn

I love the ocean. The ocean sounds like war.

And I love salt, and lemon, and wounds healed with liquor.

And the trumpet. The trumpet is a mad

bitch in my heart

who makes me strong.

I say goodbye to them, to the cliff that's mine

and the long night and the greenish pill

and the memory of an older man

who first saw me bare

my wrists.

I say goodbye to them: to the blade

that moves gently as a wave, to the sea of blades

and flames

and to the drink that I have put my mouth upon

and drank.

I wept at my waters and at my death.

With half my life, I loved like genius in the dark;

with half my life, I clapped across a desert

where love was. And where it wandered. I was

a weird fish that walked--

I grew lungs

and hooves and hair.

I no longer fingered my gills.

I began to shave my face.

I was a stranger to myself and I longed for it.

I longed for the ocean

and when I couldn't have it

I went mad--I bleated

until the horns sprouted from my forehead

until I butted the stone wall

at the bottom of the cliff

that I wanted to throw myself from.

I was my own mad goat

in love--

Goodbye, I thought. So long.

To the coast, to the landscape of my orphanage.

I will eat myself.

I will thank no one.

. . .

next interview: Joshua Poteat

. . .