28 DEC 06

How has your first book changed your life?

45. Katie Peterson

How did your manuscript get picked up by New Issues--did you win a prize? Had you sent it out much before that?

My manuscript was chosen for the 2005 New Issues Poetry Prize by the poet William Olsen, who wrote me an introduction that makes me blush even to think of and who has treated me with such incredible kindness and respect. Bill called to tell me I was a finalist and then left a message on my phone to tell me I had won the prize. It was my second year sending out the manuscript; I had been a finalist for a few other prizes (Alice James, Contemporary Poetry Series) and I suppose I'd sent out the book less than 20 times total in those two years. I wasn't aware of the New Issues contest the first year. It's hard to keep track of so many contests. But I later learned that a number of poets I had admired--Malena Morling, Claire Bateman--were New Issues poets. I was worried that the book was Romantic and autobiographical in subject matter but experimental, obsessive, and blunt in tone--that more traditional contests and presses would be put off by some of the unfinished thinking in the book and that experimental contests and presses wouldn't find the work formally pyrotechnic enough. New Issues, their judges, editors, and poets, seems to have a truly democratic (and I mean eclectic) sensibility. Their books have deep unity as books but privilege the individual poem; I like to think my book fits in well with their list.

What do you remember about the day when you saw your finished book for the first time?

What I remember is the night before. I was having dinner with my wing-girl Chiyuma Elliott (a gifted poet herself), and a friend, a generous and wicked-witted poet from San Francisco, and that poet's mischievous wife who is the quintessence of fun. And some new friends too. What I remember is that at a certain point, after much carousing and my continued protestations of "this doesn't really matter to me that much" (what can I say? I come from Irish immigrant stock, the self-criticism is at the level of the marrow in the bone), that poet said to me that I needed to enjoy this, to appreciate the moment, to really think about it and reflect on it (though he didn't use the word reflect and I can only imagine what he'd say if I accused him of such Californification of psychology). I can't for the life of me remember what he did say, actually. But I remember feeling, at that moment, punched into the gang of Poetry. When I looked at my bleary eyes in the mirror the next morning I thought: you wrote a book. And I believed even less that "I" had done it, but even more that the damn thing existed and couldn't be destroyed, and that even if it could be destroyed, it would have been. This was all before I saw the book. Then Chi and I walked over to the Austin Convention Center and there it was. When it was in my hands for the first time, it felt out of my hands. It was a hell of a lot more like releasing a bird or taking out the trash than possessing something.

Were you involved in designing the cover?

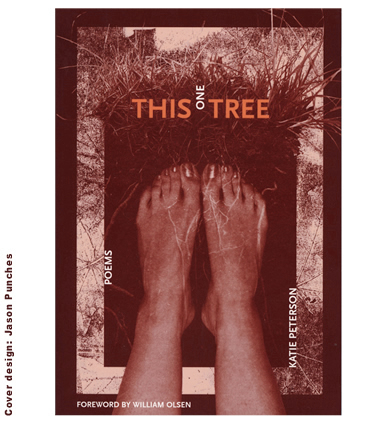

No, not in the least. And do you know what? I felt it to be a relief. I don't know anything about design. I know what I know, but I don't know anything about that. I can see myself wanting to get involved in those things in the future but felt strangely grateful to have the burden lifted from me. I was completely flabbergasted when I saw the cover. I think the book has one foot in fall and one foot in spring for a reason: "now no matter child the name / sorrow's springs are the same," as Hopkins says. And there are two feet on the cover, actually. But I expected the designer to love the spring part of the book more than the fall. I love the contrast of the orange and the black and the drama of the interior title page with its tuft of earth. The designer, Jason Punches, clearly read and interpreted the book, and his deep reading is a great compliment to me. It is a reading, too, that registers the book's obsession with opening up the earth and getting inside it, restoring the body to its place in the seasons, and me trying to do that, as William Olsen says, "on behalf of" the reader, who is entreated to stand in the book. I like the made quality of New Issues' designs, and their lack of reliance on single photographic images.

Before your book came out, did you imagine your life would change because of it?

I imagined I would have an easier time getting a job. That has a lot to do with why I sent the manuscript out in the first place. A lot of me would have been at peace with holding onto my poems forever, or at least for a very long time, but I have a career as a teacher too and I have to make a living and I needed to get out there. On a different point, I imagined that the person I was in a relationship with when I wrote those poems would want, at some point, to talk to me about them or re-initiate our friendship.

How has your life been different since?

When people ask me what I do I can say I'm a poet and prove it because I have a book. It makes it simpler to explain myself. I spent half a decade writing poems while completing an academic doctorate at Harvard University; I have to say that I have wonderful colleagues and friends from that time who respected and admired the fact that I wrote poems. But it wasn't always easy to make art in an environment for making criticism. A book is a kind of currency of respect and I'd be lying if I said I didn't feel that when This One Tree came out.

Probably more significantly there's been quite a change in the way I perceive myself in relation to my work. Before the book I guess I mostly hid under the silly title of "Graduate Student Who Writes Poems." Now, in December 2006, doctorate in hand and book on the shelf, I'm a poet with a PHD. Note the reversal of self-proclaimed priorities.

Were there things you thought would happen that didn't? Surprises?

I thought my parents might get mad about how they were portrayed in the book.

I thought my ex-boyfriend might get mad about how he was portrayed in the book.

I thought some other people in the book might also get mad.

I thought I would want to edit the poems after they were published.

My parents were hilarious about the whole thing and probably don't even understand how funny the statements they made about the poems they were in were. My ex-boyfriend came to a reading I gave in Cambridge and was very sweet to me about the book when I ran into him in a coffee shop. Some other people got mad; some other people never read it so don't know what I'm talking about. I don't want to edit anything. The book is finished.

What have you been doing to promote the book, and what are those experiences like for you?

I did my first reading as a job talk for a job in the Midwest I didn't get. It was thrilling and there was a Q&A where people asked me wonderful and weird questions. I did my second reading after the book came out in Cambridge at the Grolier series for Louisa Solano. I started teaching at Deep Springs last January and flew to Cambridge for 36 hours to get the signatures for my dissertation and to do this reading in April. Getting the signatures on my dissertation was an incredible feeling; after doing that I had dinner with some friends at a place I've been so many times I've lost count and then went over to Adams House where I'd seen Louise Gluck, Donald Hall, Franz Wright, and so many others read. When I looked out at my friends from the eight years I'd been in Cambridge it became clear to me how connected I was to my poems. I read the middle section, all the poems called "The Tree." In October I read at Prairie Lights in Iowa City to an intense, focused, wonderful crowd; I was staying with my friend Kevin Holden and had just met Brenda Hillman, with whom I had remotely co-authored a wonderfully experimental critical essay on Emily Dickinson. Reading in Iowa with her present and a group of committed young poets present was one of the highlights of my year, an unforgettable experience.

As you can see by this narrative, I have been focused on the personal revelations of self-promotion, not the thing itself. I haven't sent my book to countless journals or been as assiduous about courting reading opportunities as I could be. The thing is, I've been living in the middle of nowhere, teaching at this school in a remote location and focused on my work, focused on writing new poems and teaching and being a part of this community. It may be the Sagittarius in me whose blind optimism thinks that the book will find its readers and reviewers. It found you. It may be the self-effacing Irish Catholic, the withdrawn Swede, the woman, the moralist, the coward in me that still shrinks from self-promotion. It may be the tired person who got her doctorate this year that has fallen short of her responsibilities to her work and her career. But I wrote my dissertation on Emily Dickinson, who was not much for publication but a great one for ambition. I like to think of myself the same way, but nowhere near as good of course.

When you say "teaching at Deep Springs," do you mean the all-male college in the desert? How is it to be teaching in an all-male school?

Yes, Deep Springs is in the desert, four hours north of Las Vegas. It is a fantastic adventure to be involved with such an improvisatory, unpredictable institution. Teaching at an all-male school--usually I don't think of it that way. In the sense that "teaching at Deep Springs" is how I think of it, which includes isolation, small class size, etc. etc. I figured out early on it's better not to be too self-reflective about my position as a woman teaching at an all-male institution. I think I prefer to just get in there and do the job. It is difficult to determine whether the fact that they're male and I'm female reinforces a separation between us or breaks down that separation more quickly. It is important to me that there are other women on the ranch (staff members, community members, though unfortunately no faculty) to create a small women's community.

What advice do you wish someone had given you before your book came out? What was the best advice you got?

The best advice was the "warning" I got from the person who is my most significant mentor and friend: that the book coming out was going to affect my ability to write for a while. I finished This One Tree a while ago--even four years, I think, maybe more--but its publication still shut me down a bit. I looked at my new work and wanted it to be like my old. I forgot this advice and then I remembered her saying it and felt relieved. It makes sense that publishing a book is like a little heart attack in your writing core. Coleridge talks about making the subjective objective, which is what you do when you go into language. When you see a book, that "objective" becomes a vivid thing, something irreducible, and language doesn't seem as plastic, as fluid, as it has to seem at least at times when you're working with it on the page.

What influence has the book's publication had on your subsequent writing?

I'm not sure but I love the feeling of reading new poems at readings, and I wouldn't be doing readings except for the book, so I feel this wonderful desire to keep creating work which is sometimes an anxiety and sometimes something deeply felt and true. Unlike, it seems, a lot of people, though, I still work at the level of the poem and of the next poem, not the next book. I'm having a lot of trouble forming my last few years of material into manuscripts I'm happy with, and I long for This One Tree's sequential clarities. So many of those poems were written as series--I would get onto something like a roller coaster or more like someone putting me in a shopping cart and pushing me around the parking lot and just hang on tight. Now, it's all being produced poem by poem. But the book's publication made it feel like a finished act of mind, and I'm more ready for something new than I've been in years. I like the end of the book because it feels like an ending. I like what I'm writing now because I can feel how bare these poems are in comparison to the poems in the book, how full of a certain emotional sense of the desert and isolation.

How do you feel about the critical response so far and has it had any effect on your writing?

Critical response? Am I missing something? A nice guy in England put a review on his blog. I was hoping that after I reviewed Legitimate Dangers for the Boston Review someone would review me but maybe I should have been meaner to that anthology. That appears to be what you have to do to get attention these days. Of course, not that much time has gone by, and since the book was just published in March perhaps I shouldn't expect anything. I wonder though, since so many reviews these days are just struggling to tell us how to read the poems how much effect it would have had. This is less to slam reviewers or poets than it is to point out that a lack of a culture of value-driven discernment when it comes to poems means that reviews serve a different purpose and often these days serve merely to introduce the reader to work or a way of building a poetics or even a subject matter; or they seem to err on the opposite side and be formulations of ego without personality. I love critical reviews when they're proven, argumentative, and eloquent; Maureen McLane's reviews are like that. If someone took the time to read the book and review it I would be overjoyed--that's how I felt when I found out this guy in England wrote about it. That's how I felt when I found out that the Harvard advocate staff had used the book for their spring Comp & the editor, Casey Cep, handed me a bunch of essays about the poems. I read those essays sometimes recognizing with joy the concerns of the poems and sometimes utterly baffled and sometimes humbled by the lesser moments pointed out to me by strong readers.

I should say that the three poets who wrote cover statements for the back of the book did lovely jobs, all of them, and that William Olsen wrote me a wonderful introduction. These critical responses came at a wonderful time. I know blurbs have a bad name in the poetry world, but I am grateful those people felt confident enough to stand behind my work.

Do you want your life to change?

I want to continue to be changed by extraordinary people and significant experiences. I am lucky to be in a situation where that happens often.

Is there something you're doing now that you think will bring about a change that you seek?

This is a very spiritual question. It is like a fortune-teller question.

I am looking for a job. It is the Wheel of Fortune. I am reading deeply in the Romantic poets and remembering, reconstituting, re-experiencing their faith in experience, language and the soul, and the idea that poetry is a transaction of ideas that needs individuals. I am buying all of it, recklessly and enthusiastically, from beauty being truth and truth beauty to Thoreau thinking that in wilderness is the salvation of the world. I am reading not as someone who might write an article but as someone asking questions. Some people think the greatest enemy to beauty in this world is reality--that it's hard to make beauty or perceive it with all the ugliness going on. I think the greatest enemy to beauty is time, just as it ever was, though it's speeding up on us more quickly now and we see that in the calendar of the earth growing warmer and our skeletal calendars making us live longer, it is still true and indeed even more true that we, and this, and all of it, is perishable. I want to continue to read and write with intensity and I want to use my current isolation from the world as long as it lasts to purge myself of empty critical languages, re-ignite my commitment to poetry as a form of knowledge and memory, and look very closely at everything around me.

Do you believe that poetry can create change in the world?

I once heard Helen Vendler say that poetry will not make you a better person but it will help you live your life. I like the way she said that and I think I believe that. If poetry makes change it does it soul by soul; it is more likely that it helps you survive.

:

2 poems from This One Tree by Katie Peterson:

At the Very Beginning

When I named you I was on the verge

of a discovery, I was accumulating

data, my condition was that of a person

sitting late at night in a yellowing kitchen

over steeping tea mumbling

as his wife remotely does the laundry.

My condition was that of a mathematician

who cannot put the names to colors,

who, confusing speaking and addition,

identifies with confidence the rain

soaked broad trunked redwood tree (whose

scent releases all of winter) saying as he passes one

Adam and Eve in the Evening

Our animal is so peaceful, he looks as if he were dead.

Tell me again how we met.

Tell me the story of your life.

I've caught something. Are you coming down with it?

The workmen outside work for no set time.

Close your eyes. What color are my eyes?

Tell me whether I should wake you early.

Asleep the animal looks less like a cat.

Tell me what to think.

Whether the weather will be fine tomorrow.

What color the thunder might render

the sky. Even if it won't be.

In summer your ribs show through your shirt

almost. Say

there has never been another,

that it is time for me to take your glasses

off, that I should never wake you.

How long have you been living in my breath?

Look at me like you want me to speak.

I do not know that there are things you think.

. . .

next interview: Jean-Paul Pecqueur

. . .