4 Aug 06

How has your first book changed your life?

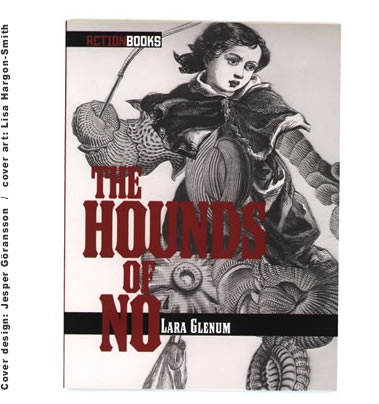

21. Lara Glenum

How do you feel about the critical response to The Hounds of No, and has it had any effect on your writing?

I've been totally stunned by all the positive press. I'm still convinced I'll be eviscerated. I've always wondered why people go to Quentin Tarantino and Lars von Trier movies in droves, devour everything Radiohead puts out, and then go home and read lame Wallace Stevens knock-offs. It makes no aesthetic sense (not to mention political sense). So I'm glad to find that people also like poetry books that act like a crash site.

Before your book came out, did you imagine your life would change because of it?

I was pretty worried about what it would do to my psyche as a writer, having to live in the shadow of this thing (even if nobody else ever noticed it). I was worried that the gestalt of Hounds would overdetermine my future work.

How has your life been different since?

A tough question to answer, since my daughter Sasha was born only a few months before the book came out. Between having a new baby and being on a whirlwind book tour and trying to finish my PhD, etc., I've had a blowout of a year. A thoroughly delightful blowout, but it's been totally over the top.

Were there things you thought would happen that didn't?

I thought I'd get slammed in the critical press right off the bat. I thought people might mistake the very stylized violence that surfaces in my work (or rather, comes leaping out of it) for actual advocacy of violence rather than a critique of it.

I also thought people might think that I level all this grotesque, over-the-top material at them just for shock value and miss the ethical and political stakes in my work. That hasn't been the case, though. I've been amazed at how well people have articulated what's at stake in my work.

Do you believe that poetry can create change in the world?

More than anything, I believe in poetry's ability to change us by disrupting our habits of language and image-making. I believe in poetry that takes tremendous risks, poetry in which the stakes are extremely high, poetry that connects with the perpetual state of emergency we find ourselves in. And it's not just the current political climate I'm referring to. Being embodied in flesh that decomposes and that is inscribed with all manner of cultural values not of your choosing is also a state of emergency.

At the same time, I don't believe in teleology, in some utopian end toward which art is nudging us. I do, though, believe very strongly in art's ability to crystallize enormously complex questions, testimonies and visions that might not otherwise be articulated.

What do you remember about the day when you saw your finished book for the first time?

I strolled up to the Action Books table at a CLMP book fair, and this guy was leafing through a copy of my book, muttering "O my! O my!" and looking thoroughly scandalized. Johannes was laughing his head off and tossed me a copy. There it was, The Hounds of No, licking its fur, already a separate animal, living a life apart from me.

How involved were you in creating the cover design?

Very involved. I chose the art--or rather I commissioned the piece from Lisa Hargon-Smith, who does these gorgeous, trippy Max Ernst-like collages (only they're not sexist and because they have no background, they scrawl their excesses against a deep silence). Jesper Goransson, who does the graphic design work for Action Books, managed to whip out the exact font I'd been hoping for--very 19th C. saloon. I generally think his graphic work is brilliant.

What have you been doing to promote the book, and what have those experiences been like for you?

The book tour has been the main thing, and it's been raucous, good fun. I've met so many brilliant people in these last few months. I've mostly been touring with Arielle Greenberg, whose second book is also out from Action Books, and Johannes Goransson, who's been reading from his wickedly smart translations of the Swedish poet Aase Berg. Sometimes Aase herself has come all the way from Sweden to join us, which floors me, since she's one of my very favorite poets. Even after months of touring, I could still sit and listen to Arielle and Johannes read a million times over; their work (and Aase's) is so compelling and multi-valent, I never get bored. And Johannes is totally hilarious.

What advice do you wish someone had given you before your book came out? Or, what was the best advice you got?

I really couldn't ask for a better pair of editors than Joyelle McSweeney and Johannes Goransson. They've done so much to make things go smoothly for me. And their vision for Action Books is really stunning--no one's publishing the outlandish, risky books that they do. They saw a vacuum in the publishing world and leapt into it with a war whoop. They've got a fantastic pair of editorial eyes (two fantastic pairs), and I feel extremely lucky to work with them. They've advised me all along the way.

What advice would you give to someone who is about to have a first book of poetry published?

Don't think about it too much. Don't let the novelty/anxiety/thrill of it take you away from your real work, which is writing more mind-boggling poetry.

What influence has the book's publication had on your writing?

I can't say. Or rather, I'd prefer not to think about it just yet. I'm trying hard to exist apart from Hounds now, at least in my writing.

Do you want your life to change?

I'd like the American empire to deflate without me and everyone else having to die to accomplish it. I assume this desire isn't unique to me.

Is there something you're doing now that you think will bring about a change that you seek?

Very hard to say. I'm trying. See above.

:

A poem from The Hounds of No by Lara Glenum:

The Name of the Ghoul

As the signified marched down to the harbor to embark, the

streets through which it passed were lined with corpse-like

effigies and exploding coffins, and the air was rent with the

noise of the machines wailing for their dead language.

The child first entered the Symbolic register upon learning

the name of the Ghoul.

Christ signifies "the void in all things." The floating signifier,

by whatever name it was known, was often represented, year

by year, by human victims slain on the harvest field.

The men slew the god of language, grinding his bones in a

mill, while the women wept crocodile tears.

Then the dead were believed to rise from their graves and go

about the streets, vainly endeavoring to enter temples and

dwellings, which were barred against these disturbed spirits

with ropes, buckthorn, pitch and siren-like sequences of non-

meaning.

When the Emperor Julian made his first entry into Antioch,

he found that even the gay, luxurious capital of the East was

plunged in mimic grief for the death of the signifier.

It is conjectured that the cross to which Christ was crucified

was actually language god's enormous wooden tongue.

. . .

next interview: Jen Tynes

. . .